When police entered Ed Gein’s farmhouse in November 1957, they expected to find a missing woman. What they uncovered was something closer to a nightmare: skulls used as soup bowls, a belt made of human nipples, masks stitched from women’s faces, and a chair upholstered in human skin.

And yet, amid the horror, Ed Gein was charged with just one murder.

That charge was for the killing of Bernice Worden, a hardware store owner who vanished on the morning of November 16, 1957. Her son, Frank Worden—a sheriff’s deputy—found blood on the floor and an open cash register. The last receipt in the logbook showed a gallon of antifreeze, sold to one man: Ed Gein.

Later that evening, investigators searched Gein’s remote property. In a shed, they found Bernice Worden’s body—decapitated, gutted, and hung upside-down. Inside the house, they found her heart and her head in a burlap sack. It was a scene so grotesque that seasoned officers vomited in the yard.

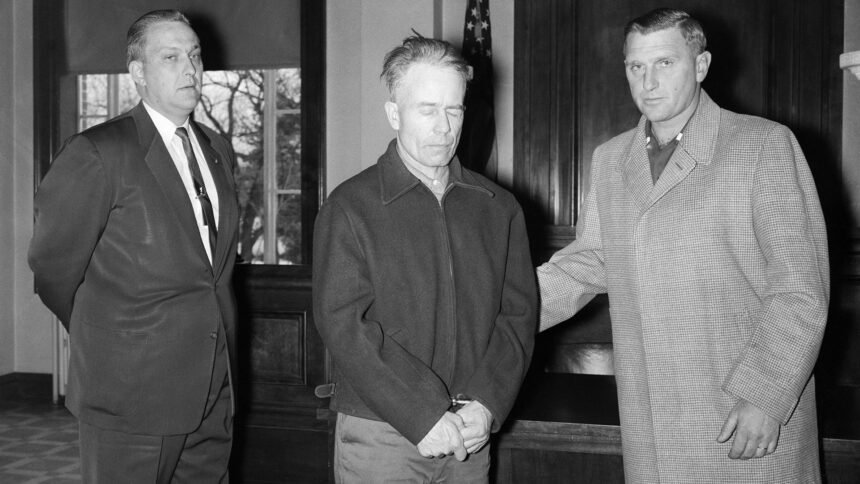

Gein confessed to the murder. He was arrested, institutionalized, and would never again live outside a mental hospital.

But Worden wasn’t the only woman to disappear.

The Woman in the Paper Bag

In 1954, Mary Hogan, a 51-year-old tavern keeper in nearby Pine Grove, vanished without a trace. Blood was found in her bar. Locals whispered her name for years, but no one was ever arrested.

That changed when police searched Gein’s kitchen.

Inside a paper bag was Mary Hogan’s face, peeled from the skull like a rubber mask. Later, Gein would admit to killing her, though his stories changed depending on his mood and medication. Sometimes he said she died instantly. Other times, he said he didn’t remember.

Despite the confession and physical remains, Gein was never charged with Hogan’s murder.

The reason? Prosecutors already had a solid, recent case: Bernice Worden. With Gein ruled legally insane and confined indefinitely, the state chose not to pursue a second trial. Officials quietly concluded there was nothing more to gain. No additional prison time. No death penalty. No chance of release. Just more trauma for the public—and more headlines for a killer who’d already become a myth.

The Ones Who Vanished

Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden are the only confirmed victims. But Ed Gein’s name became entangled with a string of unsolved disappearances in central Wisconsin throughout the 1940s and ‘50s—cases that never resulted in charges, but never faded either.

Here are just a few:

● Evelyn Hartley (15) – La Crosse, 1953

A high school student vanished while babysitting. Blood was found in multiple rooms of the house. Her shoes were discovered in the basement. The case drew national attention, but no body was ever found. Some investigators later speculated about a Gein connection. La Crosse is over 130 miles from Plainfield—far, but not impossible.

Gein denied involvement, and no evidence ever linked him to the Hartley case.

● Victor Travis and Ray Burgess – 1951, Plainfield

Two local men reportedly went drinking with Gein. According to town rumors, they were last seen with him—and then never seen again. But no bodies were found, and no formal investigation ever produced proof.

● Other Missing Persons

During the search of Gein’s property, authorities catalogued remains from at least 15 different women. Many were traced to graves Gein had robbed, but some bones and skin could not be matched to any known burial. Whether they were exhumed from unmarked graves or belonged to murder victims remains unknown.

Gein himself claimed most of the body parts were stolen from cemeteries during late-night visits in a trance-like state. He kept obituaries and grave maps. Police confirmed signs of multiple exhumations in local cemeteries. But not all the remains were accounted for.

Why They Didn’t Push for More Charges

Legally, the decision made sense.

Gein was:

Found guilty but insane for Worden’s murder

Committed for life to Central State Hospital, later Mendota

Diagnosed with schizophrenia and sexual psychopathy

A public figure of horror, already condemned by public opinion

Trying him for Mary Hogan—or anyone else—would have meant digging up traumatizing evidence for no additional penalty. Wisconsin didn’t have the death penalty. And Gein would never be released.

Former Waushara County Sheriff Art Schley, who led the investigation, said years later, “There was no point in going any further. We had him. That was enough.”

A Legacy of Horror and Unanswered Questions

Ed Gein died of cancer in 1984, aged 77. He never stood trial for Mary Hogan. He was never linked to Evelyn Hartley or any other missing persons. But the rumors never stopped. The souvenirs never made sense. The skin masks, the nipple belt, the box of vulvas. The furniture made from bodies.

And the biggest question remains unanswered:

Were there more victims—people the law never counted, and Gein never named?

We’ll likely never know. What’s certain is this: Ed Gein was charged with one murder. He confessed to two. He may be responsible for more. But in the end, justice came quietly, with a single conviction and a long descent into madness, locked behind the walls of a hospital no one could imagine and no jury could forget.

Leave a Reply